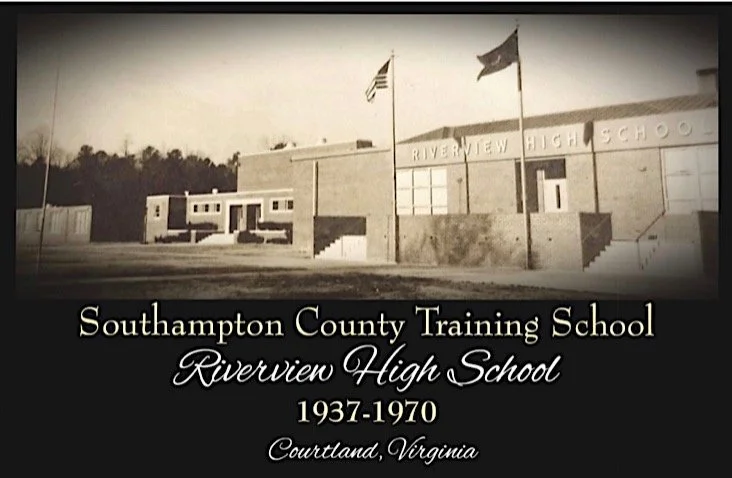

The Black Experience We Left Behind

“Stepping Stone to a Promised Land”

By Dr. Latorial Faison

VSU Assistant Professor & VA Humanities HBCU Fellow

Author of The Missed Education of the Negro: An Examination of the Black Segregated Education Experience in Southampton County

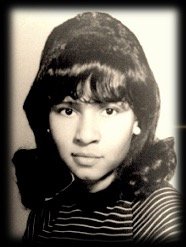

Dr. Lillie Faison as a High School Senior

Dr. Lillie Faison entered Riverview High School in rural Southampton County, Virginia, in the fall of 1962 as an eighth grader. The oldest of four girls, she went on to graduate sixth in the class of ‘67. Faison’s parents were hardworking, another average Black family in Southampton County, except they were landowners. They were farmers of their own land. Her father worked at the Union Camp paper mill in Franklin, Virginia. With their mother working by his side, he farmed their land and worked at the mill for more than 25 years. Her mother worked the farm and kept the house while she and her sisters were in school. Faison and her sisters worked on their farm after school and during the summer. After her father decided to rent the farm out, their mother worked two jobs. Later, she began providing childcare in her home, starting with Faison’s children, her own grandchildren. Over the years, she kept 49 children before retiring.

Education in Faison’s home was twofold, academic and spiritual. Her mother taught them Christian education, about Jesus, and the importance of having religion in their lives. Faison recalls, “She said that the only way that we would be able to succeed would be to behave Christ-like, and in behaving Christ-like, we wouldn't make tragic mistakes that we would not be able to come back from.” Faison’s academic education began in her small town, and she reminisced on how it had been infused with the spiritual. “When I was in elementary school . . . a two room, yellow school, we had prayer, Bible verses, and the Pledge of Allegiance before lessons.” After completing seventh grade there, Faison began her Riverview experience.

Over the years, Faison developed her own ideas and theories about what education was for Black people, for education had not been just about school and books or reading, writing, and arithmetic for her and her sisters:

Education was seen as the way out of poverty . . . the only way out. Education was a must in order to get out of the field of labor. Education was a must to move beyond Southampton County, to have a professional job. My father showed me Hampton University in an Encyclopedia that he bought for us, and he told me that he wanted me to go to that school because if he had had an opportunity, that's where he would've gone.

Faison shared that the school climate at Riverview was “warm and friendly.” She had not known anything but segregation growing up in Southampton County, so life at Riverview was her normal. She recollected that “there were poor Black students, some middle-class students. Teachers were caring and helpful. It was like a family. When one hurt, everybody hurt. When one was happy, everybody was happy.”

Riverview High School Student Class Photos, 1967

Faison found tremendous joy in the extracurricular activities that the Black segregated Riverview High School offered. She “could only participate in the ones that didn’t cost money.” She was in the school choir, the Math Club, the Science Club, the Student Council, and the National Honor Society. Faison iterated that the clubs were so beneficial because they allowed students to work on projects and to compete at other schools. She remembered one of her favorite projects, The Cone, which she presented at Virginia State University in a competition and won third place. In the late 60's, trips like this one gave Faison the opportunity to, for the first time, visit college campuses. The choir was very exciting because it also led to visiting college campuses for competitions — Hampton Institute to be exact. Hampton was the college Faison wanted to attend. She even recalled the importance of the dress code for choir competitions: “the girls had navy blue dresses and wore black shoes and skin-colored stockings.” Their director, Mrs. Harrison, was serious about presentation and requiring that they look their best. “The Riverview choir never disappointed,” she exclaimed. “We killed it every time! Our choir was outstanding. We often sung religious songs in the choir. We always, always won!”

On a more serious note, Faison recalled the foundational, true importance of her Black educators at Riverview. She said of Riverview teachers: “They were real,” and they possessed the ability “to speak truth to Black students.” She added that these teachers “talked about life as it really existed. Didn't sugarcoat anything.” Faison pointed out that in integrated educational situations, they couldn’t do that, they couldn’t “give the students advice concerning life that some of them didn't get at home.” She was aware that her Black teachers had come through that stage. They had navigated their way to become teachers “so then they could come back and tell

. . . what they experienced and how they made it. They had been poor themselves, as well. They worked themselves up.” Faison asserted that her teachers could share with Riverview students what they needed to do to get out of the situations they were in financially. She believed that her only way out was “to follow the plan, and the plan was to graduate from high school and make good grades” so she could get into a college or university.

Many of Faison’s teachers, “especially Mr. Roger Myrick . . . spoke about religion and how it played an important part in the lives of African American people.” For Blacks in the rural South, church was the mecca for Black families; it was integral to the Black community. It was the place of worship, but it was also a place of social, political, and economic information sharing. Riverview High School was even more integral to the Black student because they spent several hours a day there; more time was spent in school than in the Black church, depending on one’s age. School and church were often like one and the same, intersecting and reinforcing one another. Many of the teachers attended the local Black churches, so students and parents fellowshipped with Black educators, and that gave school, all the more, a feeling of family and community.

Riverview shaped lives in so many ways, and the lessons learned were not always in the textbooks — the older, used textbooks that Black schools were handed down from the white schools. Faison especially recalled a moment involving her math teacher, Mr. Bell whose teaching strategies included great lectures:

He would just close the door. And on that particular day, we knew that he was going to talk about life. And we were just so excited about it. And he would say, “You know,” for example, “You see that man out there driving that man's tractor? He doesn't own the tractor. He doesn't even own his life. He's out there driving that tractor. Do you want to be like that? Now, if you don't get your work and do what you're supposed to do, that's where you're going to end up, driving the man's tractor. Chopping in his field.”

Faison expressed how she loved those lectures. In addition to teaching students about life and how to navigate Black life in a white world, “Black educators could be examples of what Black students could be.” They could be “models for Black students in their dress, in their behavior, and in their motivations.” Teachers were concerned about their students’ futures; they were the students’ biggest cheerleaders and mentors. According to Faison, they were “also self-revealing

. . . they didn't try to hide the fact that they weren't always where they were at that time.”

Black culture was a given and evident in the education being administered at Riverview. Faison testified that she “received a positive view of Black culture” but the white school district often limited the perspectives of Black history and excluded the teachings of “controversial people in Black history.” In fact, Faison recounted, “There was no real balance . . . [what] people mostly taught were individuals who were considered safe to discuss, people who did not rock the boat, like Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver.” It wasn’t until she enrolled at Hampton University where she learned about “Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and W. E. B. DuBois, you know, all of those people who made a contribution, as well.” Faison conveyed that learning only bits and pieces of your history, the approved, safe, or noncontroversial aspects of it was “detrimental” to her as far as knowledge of her culture was concerned. She believes that students need balance; they need to be taught the truth. But she understood the times, the Jim Crow Era in which she lived. “You know, at the time, . . . the white superintendent, you had to toe the line . . . even in elementary school, always the safe folks — George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington. You know.”

Faison emphasized that the Riverview experience influenced students of color culturally because of the teachers’ innate capacity of the cultural competence required of teachers educating African Americans and other students of color. The teachers at Riverview High School helped students to realize that they had descended from “a proud race of people” and that knowledge of self and knowledge of one’s history was crucial to their development and growth. “We are to strive to be the best we can be.” These are the lessons that Faison carried from Riverview, that as people of color, “we must be better than whites in order to compete” and always “represent the race in a positive manner. We can't let the race down.” She learned to “never disobey the laws of the land because you cannot come back from such a mistake when you are Black.” Cultural competence was a given with Black educators at Riverview; it was a bonus in a segregated school. “To the Black community,” Faison affirmed, “Riverview was a stepping stone.” It was a stepping stone to the future, colleges and universities, trade and vocational schools, etc. “You couldn't skip that stone to get to Hampton University, Virginia State.”

In terms of the school itself and what it was to the Black community, Rev. Dr. Lillie Faison explained, “It was a place of entertainment. A community.” Parents, students, and people from the community “would fill up that auditorium for plays, for concerts, for band and choir, for dances and programs, and also fill up the area for sports because people in this area didn't have anything else.” Black people had the church, of course, but the church was a place of worship.

Dr. Faison in High School

Faison noted that school was a great source of entertainment. What’s more, the Black community experienced “ownership” with Riverview High. “That school was our school.” So Riverview was a meeting place for all kinds of school activities and non-school activities; it was used as a meeting place for community groups. It was important for the Black community to feel that something they possessed was something positive, good, growing, and excellent. They embraced Riverview because Riverview was all they had outside of the Black church. At Riverview, the Black community members were stakeholders in the education and development of their future generations. It was an investment where Black people could see and reap the rewards. There was high esteem and pride in Riverview, its educators, its students, its programs, its overall meaning. But it was also a place of survival, a place of identity development for everybody involved, especially the young Black students.

Faison shared that between home and school, her self-identity was influenced and reconfirmed daily as a Black female growing into adulthood. She was taught that because she was Black, she had to be three times as good as white kids; she could not be average:

I had to be better if I hoped to succeed. I learned that I must be twice as prepared as whites. I learned that I must strive high, work hard, be honest, be obedient, learn about my culture. Information on Black people was limited. But I did know — I did learn that being good was not good enough. You had to be excellent. And that's what you had to strive for. Average was not going to make it. You had to be excellent. Education is the one thing that cannot be taken from you. Education was the path out of poverty.

When asked about white schools, in comparison to being at Riverview, Faison shared, once again, that segregation was all that she knew. She had nothing to compare it to because she “had only seen white kids on their buses” or “as they drove down the road.” She mentioned that she “would see them at downtown Boykins or in Franklin with their parents. They looked the other way. That's it. No contact. It had been total segregation.” In terms of challenges at Riverview, Faison spoke candidly about it:

Being in that world, I didn't see any challenges as far as being at the school. That school was very well disciplined, posed no fear; the teachers were very well equipped, and they had compassion, and they made the learning environment conducive to learning. I just loved it. I never knew anything about the white schools. As far as I knew, we had everything that we needed. I never heard a teacher complain about it.

Faison asserted, like most other Riverview graduates, why she had absolutely no interest in desegregating, integrating, or attending the white high school in Southampton County:

The fear of the unknown — that was the major one, the major concern about integration. No friends, no teachers, would be interested in my wellbeing. The KKK. Stories about what happens to Blacks who try to integrate. Just the overall fear dominated. I would have been horrified. I don't see how you can learn, how you can grow, fearful. There would have been so much hatred there at the school, people not wanting me to be there. There would have been prejudice with the teachers and the administrators. It would have just been a non-learning environment. Fear was a big one — the biggest one, and then, no ethic of care from the teachers seemed to be the big second reason. You know, nobody cared for you. And going from a Riverview — where it felt like family — to walking into an integrated school where there were enemies, pretty much, that would've been pretty tough. Nobody cared — nobody would care about you. I mean, nobody on your side. Can you imagine that, nobody on your side, just left out there?

The harsh realities of Jim Crow were vividly traumatic, not just for the adults who were Black or of color. These realities were just as poignant, just as traumatic, for the children and the youth who were Black or of color and forced to come of age under these societal and cultural limitations. Faison and other Riverview students, as well as graduates of Negro schools throughout the South, were the poster children, the success stories for beating the odds, for challenging systemic racism and discrimination, and for cultivating Black excellence in spite of the adversities and disparities presented by way of systemic slavery and oppression in America throughout the segregated Jim Crow South.

Dr. Faison. 2023.

Faison went on to achieve great success after Riverview High School. She enrolled at Hampton Institute, not a university, where she majored in education. She became a teacher and then pursued a master’s degree at Hampton, after which she became a college professor. Faison and her husband, Carl, raised their five children and became very involved in the church, ministry, and helping youth in the community. All of Faison’s children have attended HBCUs; she explained why:

I wanted them to go to an HBCU because of the nurturing that takes place at Black schools. Also, their first time being away from home, I wanted them to feel secure where they were. I wanted to feel satisfied with their safety, and in the 90's, I didn't feel that secure enough for my children to go to a predominantly white school.

Faison’s children had all been educated in integrated public schools from the 70’s through the 90’s. Perhaps she was trying to give her children a Riverview experience, a Black segregated education experience in which they could get what she believed they needed — nurturing, security, safety. These are the things that were left behind, in many respects, when schools were integrated. This is the Black experience we left behind. “There are less Black teachers,” Faison proclaimed, “so there are less teachers interested and concerned about those Black children.”

Dr. Faison graduating.

After becoming an ordained minister, Faison pursued another master’s degree at another HBCU, Virginia Union's Theological Seminary. She went on to found and direct a non-profit organization, The Boykins Neighborhood Outreach Center, which she operates today with her husband. Through this organization, Faison provides services for disadvantaged and underprivileged youth and families in her community. The organization reaches students from nontraditional backgrounds and setting, students situated in poverty, and those who are experiencing a lack of stability, finances, academic resources, and services; the organization picks up where public education cannot or has not reached. Faison also pursued and completed a doctoral degree in ministry and served as pastor of the local church in which she grew up. Today, she is retired from both education and pastoring. She continues to run the non-profit organization helping youth in her community. Faison adds that there are too many Black youth living on the margins who need help, help that the public schools cannot give them, help that their families cannot give. She and her husband, also a Riverview graduate, have raised their own children who attended integrated schools. When asked how the educational landscape has changed for students of color since Riverview, Faison verbalized a staggering truth about African American students and students of color in a world that is still very white in its majority, its thinking, its systemic power, control, and makeup, its privilege:

Well, when you put Black and white children together, and you know that some of the Black children have special problems at home and all of that, you can't just take time like the Black teachers used to do us, just set aside an hour to just talk about life. We lost that. No one gets to do that to them — say, "Hey, why you doing that, such and such” or “You're going to end up such and such a place if you don't stop, turn around.” That's gone. But, with the integration came the better schools with the computers and the labs and all of those things that we didn't have. So the students have better opportunities as far as technology is concerned. But that human element — that touch, from that Black teacher to that Black child, that is gone.

DR. LATORIAL FAISON is a poet, author, professor, and Virginia native. She is a graduate of University of Virginia, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University. Faison’s writing has been published extensively in the United States and abroad. This Furious Flower Poetry Center & VA Humanities Fellow is a Pushcart Nominee and finalist for the North Street Book Prize. Faison is a recipient of the Tom Howard Poetry Prize and finalist for The Cave Canem & Louis Bogan Poetry Prizes. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Obsidian, PRAIRIE SCHOONER, Aunt Chloe, PENUMBRA, Artemis Journal, Solstice, About Place Journal, Southern Women’s Review, Deep South Magazine, West Trestle Review, The Southern Poetry Anthology, and more. Dr. Faison is the author of The Missed Education of the Negro: An Examination of the Black Segregated Education Experience in Southampton County, VA, the Twenty-eight Days of Poetry Celebrating Black History trilogy collection, and thirteen additional books. Faison teaches at Virginia State University; she is married to COL (R) Carl J. Faison; they have three sons.